Lattice strain is defined as the deviation of the equilibrium spacing between atoms in the lattice of a nanomaterial. The strain (ε) is calculated as a normalized change in the lattice parameter (astrained) versus the unconstrained original parameter (aoriginal): (ε) = ((astrained – aoriginal) / aoriginal) × 100 (%), the above equation can be used to accurately assess the compressive/tensile strain strength that occurs inside or on the surface of the nanocatalyst.

Nanomaterial strain engineering involves designing, adjusting, or controlling the surface strain of nanomaterials, which is an effective strategy for enhancing their performance across various applications. The strain in nanomaterials results from changes in the bond lengths between atoms or from lattice mismatches. As a consequence, catalysts that exhibit strain effects can have altered electronic structures and active sites, leading to changes in their adsorption capacity for reactants, reaction intermediates, and products.

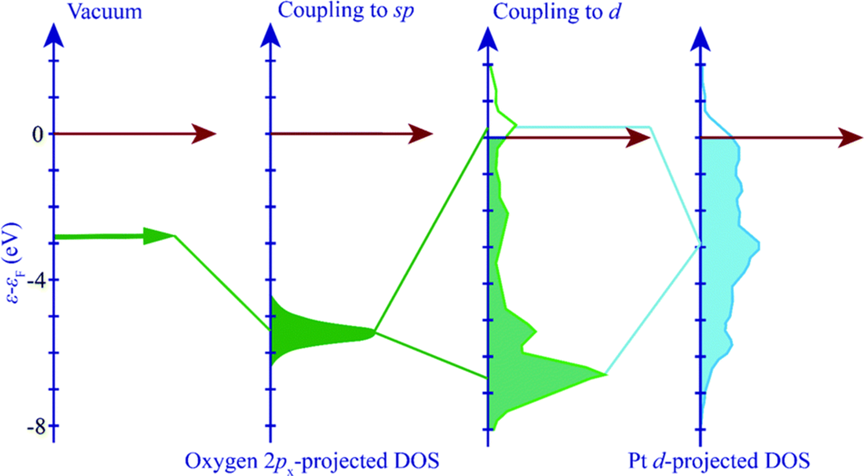

When a molecule is adsorbed onto a metal adsorbent, the valence state of the adsorbent interacts with the metal’s s-state, which subsequently couples with the metal’s d-state. This interaction between the adsorbent and the metal d-state causes the d-state to split into bonding and anti-bonding states.

When metal interacts with an adsorbent molecule, it can form both a bound state and an anti-bound state. The binding of the adsorbent to the filled and unfilled anti-bonded states is strengthened, while the occupation of the anti-bonded states depends on their position relative to the Fermi level.

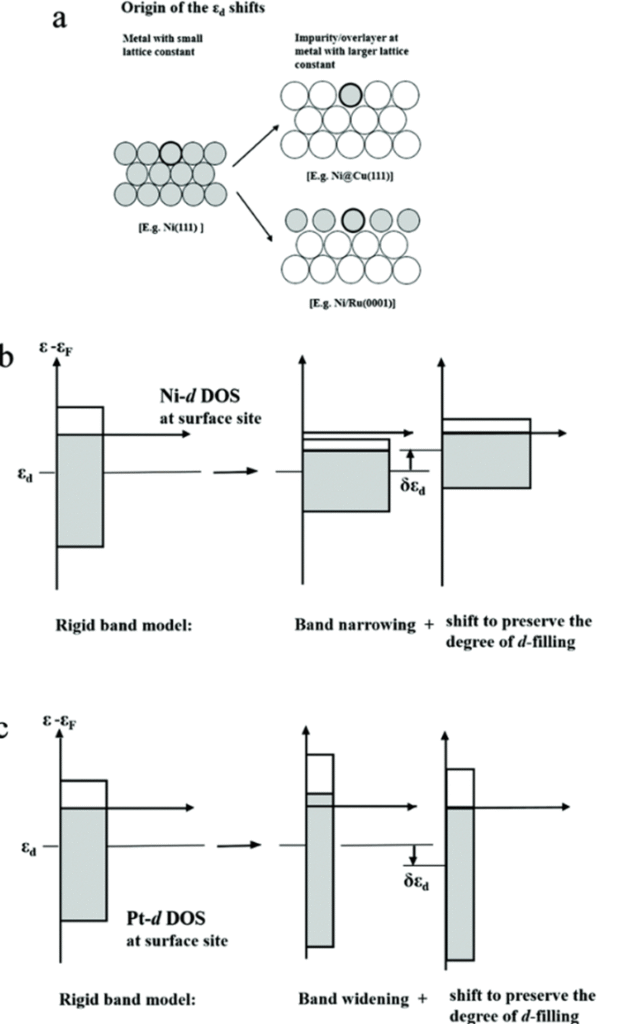

In the case of tensile strain, metal atoms with smaller lattice parameters can either be inserted into the lattice or deposited as a coating on the surface of a metal with larger lattice parameters. For transition metals, such as nickel (Ni), which have more than half of their d-band filled, the center of the d-band shifts upward relative to the Fermi level to maintain a consistent d-occupancy. As the center of the d-band rises, the antibonding d-states also move upward, leading to a decrease in occupancy and resulting in enhanced adsorption interactions with reaction intermediates.

Similarly, when platinum atoms are deposited on the surface of copper or inserted into a copper lattice, the shrinkage of the platinum lattice increases its d-bandwidth. This change corresponds to a downward shift in the center of the d-band, which weakens the adsorption strength of the reaction intermediates.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a simple and effective technique for characterizing lattice strains. When a different metal with a distinct lattice constant is added, the peak position in the XRD pattern shifts either positively or negatively, depending on whether the lattice contracts or expands.

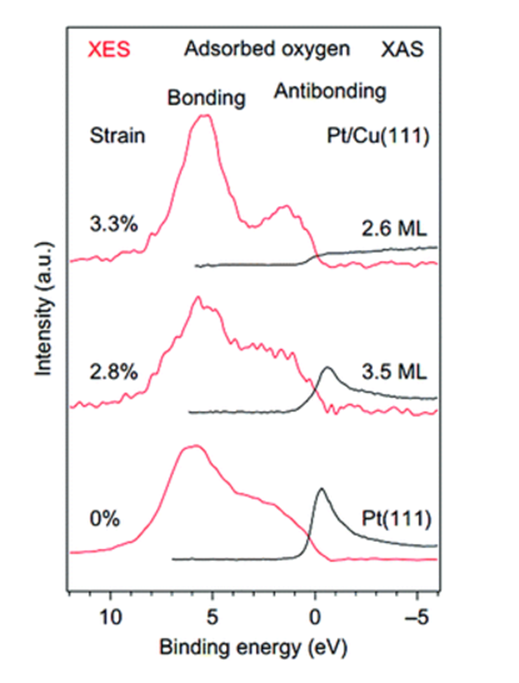

X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) are used to analyze changes in occupied and unoccupied states resulting from lattice strain, respectively. In a study examining the impact of strain on a platinum-copper alloy, it was observed that as compressive strain on the surface platinum layer increased, the antibond resonance in the XAS spectrum gradually weakened and eventually disappeared at a maximum strain of 3.3%. This indicates that the antibond state becomes fully populated, aligning with the center of the lowest layer d-band of platinum.

Nat. Chem., 2010, 2 , 454 —460Chem.Soc.Rev.,2019, 48, 3265–3278According

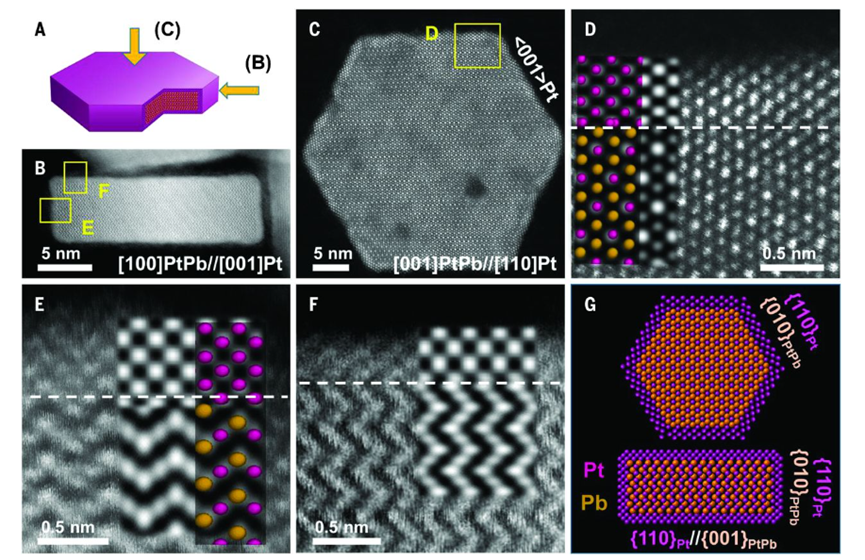

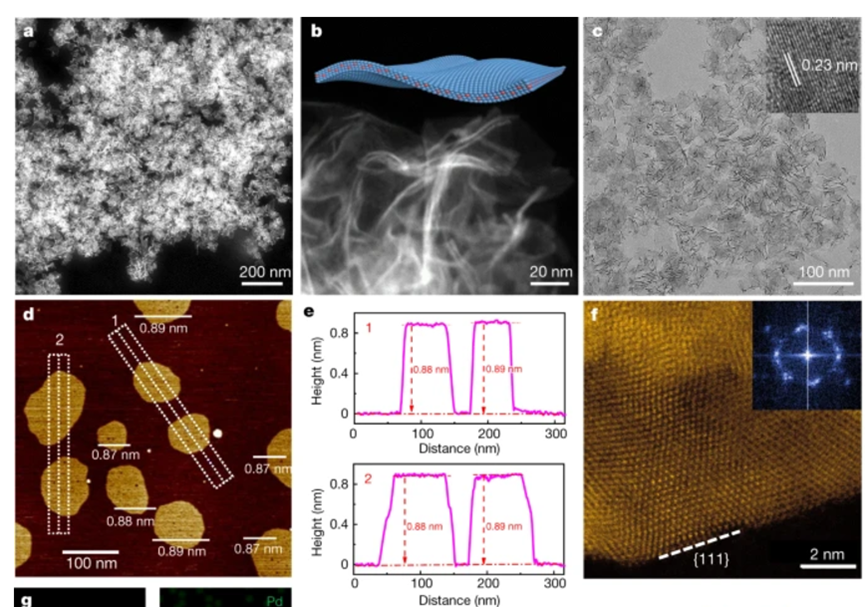

The evolution of the volcanic diagram related to Sabatier’s principle shows that the adsorption strength of nanomaterials on adsorbents can be effectively modified through strain engineering, ultimately enhancing their catalytic performance. Strain effects typically occur in core-shell structures and metal-supported nanomaterials, especially when there are different lattice parameters between the components, such as in biaxially strained platinum/platinum core-shell nanoplates.

Science. 354,1410-1414(2016).

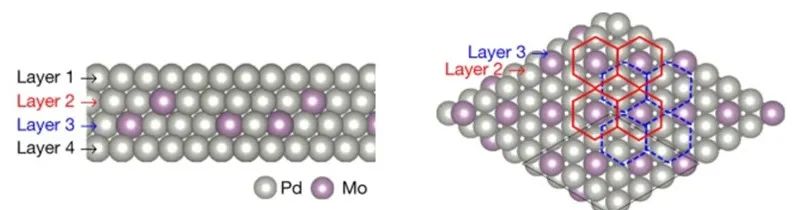

Alloys can form when metals with different lattice parameters are added to another metal, such as in the case of palladium-molybdenum or bimetallic materials under tensile strain.

Nature 574, 81–85 (2019).

Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 15, 9676–9717